December 2, 2025

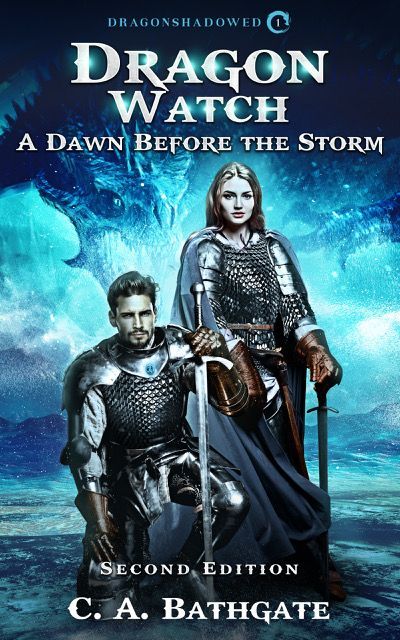

(Associated illustration from pixabay.com: used without commercial intent; Goblin forest-8727780_1280) Whether in the annuals of most fantasy books and series or role-playing games, goblins perform the role of villains and occasional protagonists or heroes. Easily deployable in any situation, goblins can be scaled down to provide a reasonable encounter for a novice adventurer, or enhanced to challenge a veteran. Hordes of goblins may be introduced as adversaries and fodder when needed in a large-scale scenario or as added muscle to bolster a villain. The possibilities are endless. As fantasy creatures, the types of goblinoids are as varied as the inventiveness of the individual dungeon master, referee and author. These may be as familiar as the goblins, orcs and uruks of Lord or the Rings, or fiendish individuals from lesser known works. Role playing games such as Dungeons & Dragons and Pathfinder present a bewildering array of various goblin types. Everything from the original gnomish kobolds of 1 st Edition D&D, through later reptilian inventions, actual goblins, orcs, hobgoblins, gnolls and bugbears. Each of these was or is currently ranked among an incarnation of ‘goblin.’ I mentioned that I take a strictly traditional approach to my adversaries and monsters in a previous blog. This holds true for my treatment of goblins, as my intellectual property is strictly within the bounds of public domain. In Valdain, the characters will not encounter kobolds, hobgoblins gnolls or bugbears—just goblins. Or ‘gobbos’ as referenced by common folk. As a nod to Tolkien, I do write about a small variation between the common gobbo and ‘greater goblins’ as mentioned in Book 1; Dragon Watch: A Dawn Before the Storm. Generally speaking, a greater goblin is much the same as any other goblin, except for their larger size, greater strength, and a penchant for order as opposed to the chaotic and wild nature of the smaller versions. From a story perspective as a writer, this differentiation allows me to present a greater individual challenge to a main character. There is very little difference between goblins. All have leathery, greenish skin; black, greasy hair; and pronounced lower fangs that often protrude over their upper lip. All goblins have a wider visual spectrum than humans. They can see in poor light or even darkness, though not so clearly as a dwarf or gnome. They dress in whatever they can scrounge or steal. Clothing, armor and weapons are always mismatched and in poor repair unless disciplined by a feared leader such as a greater goblin. Disciplined goblins become dangerous warbands or mercenary companies. Goblins don’t display much in the way of individual characterization. To quote the dwarf, Dairug, in the first novel: “Goblins are cruel and sneaky folk. Steal and play nasty tricks when they’re weak and think you’re not looking. Pillage, murder and rape when they think they’re strong. The dwarves know and have long memories. It’s been like that for many winters and even more generations. Gobbos don’t change. You might ask fire why it burns or why the day star shines. It just is.” Cruel, despised and disorganized. If goblins are widely hated, how can they appear in a seemingly endless supply? In a role playing game, this question isn’t important. As a writer of an epic high fantasy series, there should be an answer. In the world of Valdain, I rely heavily upon the works of Tolkien, who in turn based much of Middle Earth upon western myths and legends, including the epic poem of Beowulf. Readers of The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings, or those who’ve watched the movies, will note that female goblins are absent. They might assume a female goblin looks much the same as the male version. I take a different position. There is no such thing as a female goblin, at least as native to the world of Valdain. How is this possible? I rely on Tolkien and Beowulf. Tolkien mentions that goblins ‘spawn’. In Beowulf, the hero swims through a lake in pursuit of the ‘troll’, Grendel. As he swims deeper, he encounters swarms of vicious, small creatures that he ignores until he reaches air. Tolkien also makes it clear that wizards, such as Saruman or other spell casters are important to the creation of goblin armies. In the magical world of Valdain, I propose the following: Goblins ‘spawn’ much like insects, spiders, or amphibians, in the dark and wet. Filthy and vicious, they excrete at random, and their offal trickles into underground ponds and waterways. Here, goblin shamans or evil spell casters use the discarded genetic material to spawn goblins. Much like spiders in a cocoon or aquatic insects, these creatures fight and devour each other to survive. Those that crawl out of the water become new goblins. The weak and crippled are eaten. The more shamen or spell casters available, the more goblins join their limitless ranks. So what about half-goblins or hurks such as Rarnok? Dairug supplies the answer. Goblin bands raid, and will abuse human females when victorious. Most women don’t survive the experience, and most goblins are impotent. But not all. Though rare, the result is a hurk. Child hurks often appear the same as a normal human baby. If recognized as a hurk, they are killed. A young hurk seems much like any other child, but may be prone to violence. They don’t develop goblin traits until puberty, when they are usually killed or exiled. The life of most hurks is short and violent. Fortunately, all hurks are mules. Goblin culture, if it can be called a ‘culture’, is uniformly violent. What variations occur are more in keeping with their environment than the temper of the goblins. Most prefer underground locations, and will use slaves or bully weaker members into constructing caverns when necessary. Goblins can be found in mountains, hills and forests, though they shun open plains and swamps. They have been known to construct crude surface villages in heavily wooded areas. In Valdain, the northern forests and mountains are considered goblin territory. They are also numerous in the forests and mountains of the far west.